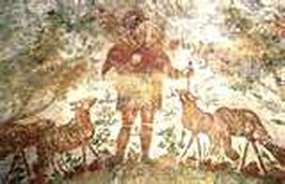

For followers of Christ, the Domitilla shepherd represented Jesus as a shepherd, based on New Testament metaphors. But for Roman pagans, the telltale harp recalled the mythical figure Orpheus, who charmed the beasts with his singing. Consequently, the Orpheus-Christ fresco, though simply rendered and presented, represented the complexity of early Christian art.

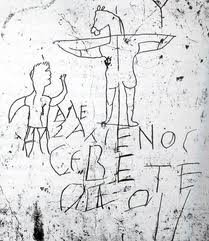

During the advent of Christianity, classical Roman art prevailed. Whether pagan or Christian, artists painted and sculpted according to this style. It epitomized the definition of good art. The best models of classical art—the rounded, idealized body—emerged from representations of Roman gods and goddesses. So it’s natural that early Christian art mimicked this style, creating figures similar to pagan models.

In addition to style, the earliest Christians borrowed common themes from the Roman culture. These themes helped pagans and other non-Christians to understand core messages of the growing faith. Consequently, Christian art compared Christ to the pagan shepherd, a god of light, and a wise teacher or philosopher.

In other adaptations in the Roman Empire and the Holy Lands, Christians used less-controversial symbols in the culture to express Christian beliefs. Christians converted pagan images of anchors, ships, and stars into images of the new faith. As a result, early Christians viewed their art in light of redemptive adaptation. Christian artists of Late Antiquity adapted what their culture understood and redeemed these images by assigning new meanings to them. With time, the adaptations represented biblical beliefs incorporated into Christianity’s own visual lexicon. Christian images and symbols meant what Christians believed about them.

Biblical Salvation Themes

Besides Roman themes, early Christian art also heartily pulled from Old Testament and Apocrypha stories and events in Christ’s life. While the Church endured intermittent persecutions, art themes centered on metaphors for salvation. These themes decorated catacomb walls, memorializing the deceased and encouraging the living. In particular, the stories of Jonah, Noah, Moses, Abraham, and Daniel relied on a redemptive message, as did less-popular images such as Susanna or Daniel and his friends in the furnace. So did New Testament stories like Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead.

It’s commonly supposed that Christians chose these narratives for the catacomb walls and sculpture because they lived in an uncertain world, at times fraught with persecutions. The most frequent images emphasized God’s ability to deliver his spiritual children from peril, either on earth or in heaven.

In the fourth century, after Constantine’s intervention, deliverance and safety images diminished and Christian mourners selected more narratives from the New Testament. Perhaps it’s because Christians no longer lived in peril, and more believers were Gentiles rather than converted Jews. During Constantine’s reign and later when Theodosius I declared Christianity the Roman Empire’s state religion, Christian art flourished.

With this transition, Christians and their art breathed freely in the Roman world and ventured into new cultures, extending into the future and finally reaching ours.

Learn more about early Christian art in Judith Couchman’s book, The Art of Faith: A Guide to Understanding Christian Images (Paraclete Press).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed