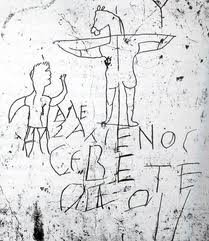

Art historians disagree whether the scrawled words should be interpreted as a Christian’s profession of faith or a pagan’s scorn. On the one hand, Jesus rode on an ass, so this animal became an important symbol for early Christians. From this perspective, some suggest drawing the crucified Christ with a donkey’s head paid

homage to a hailed Savior. On the other hand, most observers recognized the inscription as a taunt from someone who mis- understood the new religion. In early Christianity, a rumor circulated Rome that Christians worshiped the head of an ass.

What was the true meaning? Only the graffiti artist knew for sure.

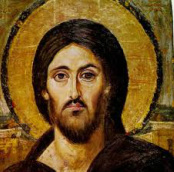

During the same era, pagans, Jews, and early Christians carved deep recesses in the soft tufa rock shaping the outskirts of Rome. From the third to fifth centuries, survivors often painted these catacomb walls with images that represented the deceased, and images of a person in prayer, the orans (Latin for “praying”), decorated several catacombs. The orans figure populated Late Antiquity, usually depicted as a standing, veiled woman with her hands outstretched and gazing toward heaven. It’s not always clear, however, whether an orans figure represented a pagan, Jewish, or Christian worshiper. Each religious group used this stance as a prayer posture.

Old Testament Jews spread their hands in prayer. From the desert of Judah, David prayed, “I will praise you as long as I live, and in your name I will lift up my hands” (Ps. 63:4). When a pagan orans lifted up her hands, she expressed “the affectionate respect due to the state, to a ruler, to the family, or to God.” Because early Christians were Jewish, they naturally practiced this stance. The apostle Paul advised the earliest Christians: “I want men everywhere to lift up holy hands in prayer, without anger or disputing” (1 Tim. 2:8, NIV 1984), and early church literature recorded the widespread practice of this prayer position.

Consequently, the famous orans in the Catacomb of Priscilla in Rome doesn’t own a clear interpretation of her origin or beliefs. As much as art historians argue one interpretation or the other, nobody knows for sure.

Like the Palatine graffiti and the catacomb orans, some of the earliest years of Christianity and its art linger in ambiguity. Even more mysterious, it doesn’t appear early Christians produced art for two centuries of the faith. As far as we know, with a few exceptions of signs and symbols, Christian art didn’t appear until the early third century. Nobody knows the exact reason for this omission, and at any moment a new archaeological discovery could prove this assumption wrong.

Just as we can’t precisely pinpoint why Christian art didn’t exist in the earliest years of Christianity, we don’t know exactly why it appeared around 200 A.D. But when paintings from this growing religion emerged from underground Roman catacombs, Christian art never turned up absent again.

Some people feel uncomfortable that early Christian art sometimes shared images with other religions. They think this either proves Christianity as a “borrowed religion” or taints its purity. What do you think?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed