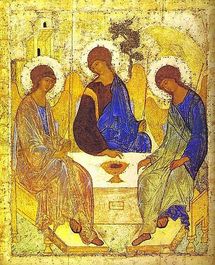

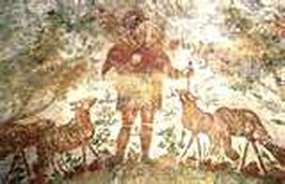

- What is the work’s title? What insight does it lend to the content?

- Who was the artist? Do you know anything about this person? If so, what? How might his or her life and other art affect this work?

- When did the artist create the work? If you know anything about this time period or art era, how might it have affected the artist or the work of art?

- What materials did the artist use to create this work? What did these materials contribute to its overall presence?

- How would you describe the artist’s style? Why might he or she have chosen it?

- How did composition, color, line, shading, perspective, and other elements or techniques contribute to the overall work?

- What was the purpose of this work? If you don’t know, what would you guess it to be?

- Was this work commissioned by a patron? How might this have affected the outcome?

- If figures appear in the work, who are they? What do you know about them? Or how could you learn about them? Why were these figures meaningful to Christians?

- What was the setting for the figures? What did this location contribute to the work?

- What symbolism exists in the work? What did it mean to Christians of this era?

- Was this work of art based on a biblical story or passage? If so, what was it? Why was it significant?

- Can you discern a lesson or message in the work of art? If so, what is it?

- How does this work qualify as Christian art?

- What is your opinion of the work? Do you like it? Why, or why not?

Learn more about Christian art in Judith Couchman’s book, The Art of Faith: A Guide to Understanding Christian Images (Paraclete).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed