To end a twelfth-century struggle between the church and the monarchy, King Henry II ordered two knights to assassinate Thomas á Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury. Angry about the murder, the populace rose up against Henry and demanded his penance at Becket’s tomb in Christ’s Church of Canterbury. Within a short time, people reported miracles at the burial site and pilgrims flocked to visit the church.

Monks feared Becket’s body might be stolen so they placed his marble coffin in the cathedral’s crypt and built a stone wall in front of it. Two gaps in the wall allowed pilgrims to insert their heads and kiss the tomb. Later the clergy moved Becket’s coffin to a gold-plated, jeweled shrine behind the high altar. Canterbury already served as a pilgrimage site, but after Becket’s death pilgrims swamped the town, increasing its financial resources and religious

prestige.

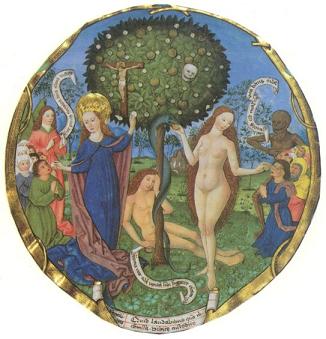

The attention afforded Becket’s burial site typified the reverence toward saints since early Christianity. When Christians thought about saints, the motto was “the closer the better.” In the earliest catacombs Christians wanted to be buried near the apostles and other saints, to assure an immediate passage to heaven, ahead of other believers. As more shrines, churches, and mausoleums sheltered the remains of saints, Christians planned trips to these locations. If they couldn’t manage an extended pilgrimage to faraway lands, they visited the

nearest saint site possible.

When the focus on dead saints and their body parts bloated into a massive industry, Christians lost sight of the sacred reason for calling selected Christians “saints.” The Church originally honored these Christians for their piety, humility, service, and sacrifice. Not for their ability to draw crowds and produce income. As Christianity grew, so did the list of sanctioned saints. The Church assigned them feast days and Christian art depicted them with symbols that capsulated their ministries and miracles. It also corrected its course and remembered the real reasons for sainthood.

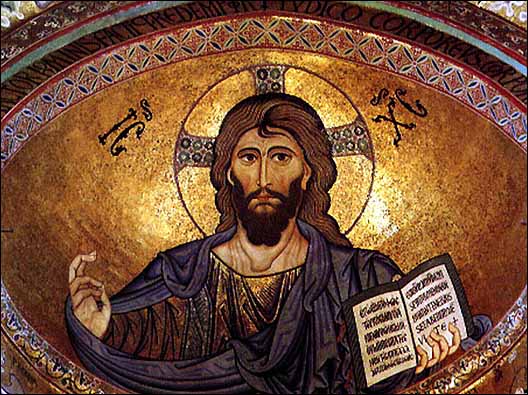

The Eastern and parts of the Western Church honored saints, both biblical and extra-biblical, and the numbers accumulated into the thousands. Some saints also earned the title, “Doctor of the Church.” Through the centuries, their teachings influenced the worldwide body of believers.

Although the Church named thirty-three doctors, both Western and Eastern Christians honored four eminent Doctors of the Church, often depicted in Christian art. These saints—also called Church Fathers—contributed significantly to the doctrine and development of Christianity from the fourth through the seventh centuries. Whatever your believe about sainthood, these Church Fathers contributed significantly and positively to the growth of the Church, Consequently, their images flourished in Christian art.

The Western Doctors

The Western or Latin Church named these four church leaders “doctors” during the Middle Ages. In alphabetical order, they are:

Ambrose. Fourth century. The Honey-Tongued Doctor. Ambrose worked as prefect of two Roman provinces and then served as the Bishop of Milan. Well-known for his eloquent preaching, Ambrose bestowed a fresh dignity and respect for the Church. He also originated the Ambrosian chant used in the liturgy. Feast Day: Dec. 7.

Augustine of Hippo. Fourth and fifth centuries. Doctor of Grace. Augustine became a Christian under the influence of Bishop Ambrose in Milan. Later Augustine moved home to Africa where he founded a monastery and served as Bishop of Hippo. He fought heretics and challenged other religions. Augustine also wrote literary works that profoundly impacted the Church. Feast Day: Aug. 28.

Gregory the Great. Sixth and seventh centuries. The Greatest of the Great. Gregory sold his possessions and converted his home into a Benedictine monastery. He also built six other monasteries in Sicily and Rome. After living seven years as a monk, the Church ordained him as a Roman deacon and then named him pope. Gregory used his papal power to denounce slavery, stop war, and develop missions. Feast Day: Sept. 3.

Jerome. Fourth and fifth centuries. Father of Biblical Science. Jerome became a priest in Rome, but eventually moved into a hermit’s cell near Bethlehem. He spent the rest of his life writing and translating the Bible into Latin, the common people’s language. His version of the Bible, the Vulgate, dominated Church study, thought, and worship for centuries. Feast Day: Sept. 30.

Eastern Doctors

The Eastern or Byzantine Church named these saints as their Doctors of the Church. In alphabetical order, they are:

Athanasius. Fourth century. Father of Orthodoxy. As Bishop of Alexandria, Athanasius fought against the spread of Arianism, a movement that claimed Jesus wasn’t equal to God the Father. One of his greatest contributions to the Church was his doctrine, homo-ousianism, that declared the Father and Son of the same substance. Feast Day: May 2.

Basil the Great. Fourth century. Father of Eastern Monasticism. Because Basil struggled with pride from success, he sold his possessions and became a monk. He founded several monasteries and later the Church consecrated him as bishop of Caesarea. Basil

possessed eloquent speaking abilities, engaged in relief work, and triumphed over Arianism in the Byzantine East. Feast Day: Jan. 2.

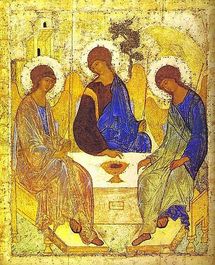

Gregory the Nazianzen. Fourth century. The Theologian. Gregory helped Basil with his exegetical works of Origen and the compilation of monastic rules. He became a priest and later served as Bishop of Caesarea and Sasima, and as archbishop of Constantinople. Gregory tried to bring Arians back to a belief in Christ’s divinity and he preached powerful sermons on the Trinity. Feast Day: Jan. 2.

John Chrysostom. Fourth century. Doctor of the Eucharist. John retreated to the desert to live as a monk. However, due to his health, he returned to Antioch two years later and became a lector. Over the years, the Church elevated him to the positions of priest and Bishop of Constantinople. John preached passionately about holy living and emphasized providing for the poor. Feast Day: Sept. 13.

Learn more about saints depicted in Christian art in The Art of Faith by Judith Couchman (www.paracletepress.com).

RSS Feed

RSS Feed